There is a weather buoy somewhere in the Pacific Ocean off the Hawaiian island of Kauai that can allegedly predict the winter weather thousands of miles away in Utah. It even has its own unofficial website. According to local lore, when the buoy records a “pop” in the wave height, two weeks later there will be a significant snowstorm in the Wasatch Mountains, where there are no less than 8 world-class ski resorts and endless places to backcountry ski.

I learned about the buoy in January. I was in Utah to ski and was complaining about the snow. One of my sons responded that the “powder buoy” was looking good and was pointing to plenty of snow throughout February. That is exactly what happened. The storm train that gives Utah the “best snow on Earth” started running with a storm coming through every 3-4 days. Over one week, it snowed 80 inches at Snowbird and Alta at the top of Little Cottonwood Canyon; one of the most avalanche-prone and active places in the world with 64 avalanche paths.

That much snow puts the risk of avalanches in the extreme category. Snowbird and Alta went into “interlodge” status. That means nobody can leave any lodge or building. It lasted a record 60 hours. The payday at the end was being able to ski untracked powder until the canyon road opened and the rest of Salt Lake Valley headed to the mountains. I know people who have arrangements with their bosses that allow them to automatically skip work in case of a big powder day and make it up later. Following the powder buoy helps them plan ahead and prepare.

Those who don’t prepare are prone to “powder panic;” the inability to concentrate, work, or focus on anything knowing that there is deep, fresh snow but that huge lines of cars waiting to get up the canyons will most likely block the way. It may not be an official diagnosis in the DSM-5, but I suspect it is handwritten on the book’s back cover in every Utah hospital. Powder panic caused my oldest son and his Minnesota buddy to recently get up at 4:30 AM in order to get to the Alta parking lot by 6:30. And they weren’t even the first ones there! Living in the Midwest and getting used to a much higher atmospheric partial pressure of oxygen has cured me of that disease. I calculated the PatmO2 at Alta to be about 25% lower than in Minneapolis.

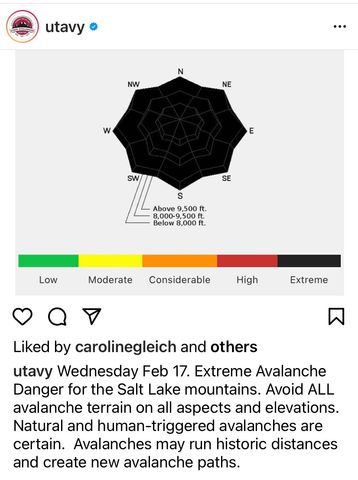

The Utah Avalanche Center publishes a daily avalanche risk report in the form of a radar graph that depicts the risk of a snow slide depending on elevation and slope direction. During the storm, it was a rare “black rose.” There was no safe place to ski in the backcountry at any elevation or on any slope direction. When my wife asked my other son if he had been in the backcountry he answered, “Mom, I’m not stupid.” I hope this gives hope to those of you with teenage boys.

These risk prognosticators got me thinking about predicting the epidemiology of COVID. We learned early that the models weren’t that helpful. The virus did what it wanted and when. People and behavior seemed unpredictable as well. Then we learned of variants with altered infectiousness and wondered how that might affect disease rates. We now know some of the risk factors for mortality: age, obesity, hypertension, and diabetes among others. But we don’t understand why not everyone with those conditions becomes ill or even develops severe disease.

Hopefully mining “big data” will eventually help answer some of these questions. Our system’s cohorting strategy has limited many variables that may make our “big data” even more meaningful.

Because prognosticating COVID is such a challenge, one of the hospitalist leaders is asked on the daily CMO huddle what his Magic 8 Ball is saying that day. Our own Dr. Osterholm has been saying that the worst 14 weeks are still ahead. However, new cases and numbers of hospitalized patients remain flat in Minnesota. My hope is that with more and more people receiving vaccines, increased vaccine production, and new vaccines coming online, we can finally keep the COVID black rose from blossoming.

Jeffrey G. Chipman, MD, FACS

Frank B. Cerra Professor of Critical Care Surgery

Division Head, Critical Care, and Acute Care Surgery,

University of Minnesota

Executive Medical Director, Critical Care Domain, M Health Fairview